Left 4 Dead 2 came out and I all but dropped every other game for it. Was it worth the not insignificant cash outlay to obtain, plus the effort to get the uncensored international version? I think so. Does that mean it’s immune to the infinite gaze of The Critic? I think not.

The first thing I noticed about the new introductory video for Left 4 Dead 2 was that it did not do the same job as the one present in the first game. That video introduced not only the characters of the game to new players, but also began the process of familiarisation with the game mechanics. Virtually every important aspect of the game for a new player to get accustomed to is demonstrated in those first few minutes. The individual weapons; the need to melee infected away from players; what each special infected does; how tanks attack, and what to do to stay away from witches – these are all subtly introduced to players through the intro video. Even pulling up survivors that have fallen off buildings is covered. In contrast, the L4D2 video, while full of sound and fury, introduces the new aspects of the game not nearly as well and doesn’t cover some of the more critical additions.

In fact, the crux of my criticism of the newest incarnation of Left 4 Dead boils down to the fact that, in many cases, it just isn’t up to the usual valve standard of passively and actively teaching players about the game. For the longest time I ignored melee weapons because when I first used them (on the opening level of Dead Centre, naturally) I couldn’t work out how to best use them while avoiding taking damage from zombies – so I went back to what I knew how to use, which was pistols.

In this, the very first level of the first campaign, players don’t start with a primary weapon, so any choice to use a melee weapon comes at the expense of a pistol and any way of, say, shooting a smoker off of a target barring actual physical attack on either the smoker or the ensnared player. By forcing a choice of pistol or a melee weapon on players, valve do not make it easy for new players to best learn how to use melee weapons. It took another player using melee weapons to great effect in versus mode for me to fully appreciate the value of melee weapons. It’s wasn’t completely obvious to me, because at first it would seem the advantage to a melee weapon is in not having to worry about ammo, but pistols already have unlimited ammo, so the real advantage actually lies in not having a timer on melee attacks. Add to that the crucial addition that it also kills infected rather than simply push them back and you've got a real reason to drop that shiny 1-hit-KO desert eagle for a cricket bat or machete.

Another aspect that wasn’t introduced well was the special ammo types, being the incendiary and explosive rounds. The way they work currently they use up the slot shared by a medkit or defibrillator in a player’s inventory, which invites comparisons to the important role played by the medkit. Health is worth its weight in gold in Left 4 Dead, particularly in competitive game modes, so when first presented with an offensive item to replace the spot of heath; my immediate reaction was “Why in the hell would I want that?” By placing it in the same inventory slot as the medkit, Valve are saying this could be worth the health you are forgoing if used right, which is both counter intuitive and runs counter to my own experience, in which it has never been the case.

While I similarly rejected adrenaline initially for its low health boost compared to pills, it’s come to be my preferred item for that slot. Similar to the above case however, there is just nothing outside of a loading screen tip and perhaps a brief onscreen mention that explains the primary benefit of adrenaline, in that it gives you not only a movement speed boost but increases the speed of all your actions by a significant percentage. Used judiciously, an adrenaline shot can be the difference between life and group death, particularly in one of the new crescendo events. Many of these require that an object be reached and switched off to stop the ravening hordes and for these events adrenaline is a significant boon - but again, that’s never satisfactorily explained, and it is left up to players to learn through trial and error or by observing other players (often in many cases only by having it used against them).

Another example of the reliance on ‘trial and error’ for teaching players is seen in the game's treatment of the new weapons – looking at them all it’s impossible to tell which ones are “better” than others, so players have to try them all until they find which ones work best. In the original game it was quite clear which weapons were better, as there was a very limited selection of them and the “tier 2” weapons as they came to be known were clearly improved versions of the starting weapons available at the start of every level. Perhaps this clarity in weapon hierarchy was merely a result of the simplicity of the original game, but simplicity can be a virtue. Faced with too many choices, from experience, I know that people tend to stick with what they know.

A similar level of “decision overload” occurred to me when first playing Left 4 Dead 2 as the amount of on screen activity, coupled with the engorged dismemberment and plethora of viscera, resulted in a visual overload. The signal to noise ratio needed getting used to, coming from the decidedly clean and sparse levels of the original game. This could go either way, as either praise or criticism, and I’ve certainly acclimated to the new levels of visual activity by now. But still, even for as big a fan of the original as I, it was quite the learning curve.

Lastly on my list of gripes, and my major concern, is the four new characters. This is entering the realms of personal preference and taste, but to me it seems that Nick, Ellis, Rochelle and Coach aren’t as memorable as the original quartet. Perhaps it’s because they are less obvious archetypes. Coach seems the closest to a recognisable archetype and for his larger-than-life personality he remains my personal favourite. Nick and Ellis both feel too similar – Nick, I know from the pre-release publicity, is ostensibly a conman but he’s much too nice and average. That aspect of his character is struggling to shine through, however and the only quote of his that has stood out for me is most revealing of that aspect of his character.

In a game recently I heard him admonish someone for shooting him, saying “You did not just shoot the man in the three-thousand dollar suit!” Nick needs to be talking about his suit way more, and Ellis needs something to give his character a similar focus. Valve has said that they wanted him to be “southern” and innocent and naive, while avoiding representing him as a stereotypical hick. While this effort is laudable for wanting to portray southern American culture in a mature light, I wonder if the character suffers for it.

Perhaps Nick’s character too suffers for being in a game as devoted to cooperation as Left 4 Dead 2. Thinking on it, it's possible that a sharkskin-suited conman could still be an appropriate character for L4D, as he could easily be cast as The Reluctant Help, much like Francis in the original. Francis was a grouch, but he was a lovable grouch, and it was always communicated that his character had your back. But how does one pull off “the lovable conman?” I guess what I’m suggesting is that Nick is not wisecracking enough for it; he’s not even sarcastic enough.

I’m probably being a little unfair on Valve here, but I think it’s actually a bit of a shame that they used up their most memorable characters on the first Left 4 Dead game. Unless L4D2 is surpassed by a third game in another year’s time (yeah right) I hazard a guess most will still be playing the second game and not the first come this same season in 2010.

It might seem from all the above like I preferred the first game to the second, having tragically fallen into the “I liked their old stuff better than their new stuff” cliché, but that’s not quite accurate. I really like Left 4 Dead 2, but it’s a functional kind of like. It’s the same kind of like as one gets for Season 2 of The Wire – it’s great that there’s more of it, but it’s not exactly what I wanted. I don’t like it for quite the same reasons I liked the original (with one notable exception, but more on that another time).

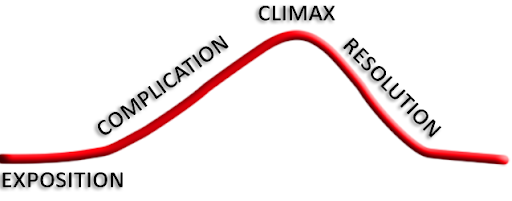

The new explicitly linked campaign narratives also fail to live up to the ‘memorability’ test, and while there are a great number of excellent set-pieces very little left me saying ‘this is like nothing I’ve ever seen before’. And that was how I felt about every single campaign of the original on first playing. Take that with a grain of salt perhaps if only to offset the nostalgia and originality of the underlying mechanics, but even so I feel the decision to explicitly link the new campaigns chronologically was unnecessary. Like all well told stories, there will be gaps in which not much happens, and they get omitted. With everything now spelt out from beginning to end and the dots all lined up and connected for us, I feel like it was a misstep.

I’m still pleased with the L4D2 campaigns, but there was something uniquely fascinating in trying to piece together the story of everything happening around you – and even to you – in the original game. This sense of a mystery to uncover has been diminished in the sequel, and that goes hand-in-glove with a lessened sense that the graffiti on the walls of safehouses is part of uncovering the mystery. I’ve looked deliberately at a number of them, but from what I have seen they have retained little of the charm of the original – notably absent are any of the pithy one-liners such as “I miss the internet” from the first game, gone too are the scribbled out notes that tell tales of ongoing discovery by previous survivors.

Still! It’s early days for the game and some of these issues may yet get ironed out. Heck, play versus for long enough and half of these complaints disappear simply because you’ll see all the tricks, all the tactics clever players have already devised and you won’t need teaching. The issue of memorable characters however remains my biggest worry. The new quartet has a lot to live up to, and perhaps that’s the biggest problem – the previous ones were so good. So good in fact, they spawned memes. How can Coach, Rochelle, Nick and Ellis possibly live up to that?